Dear UK Government, why won't you let me retire as Official Sachs Critic?

UPDATE 3: FEB 8 4:50PM: Twitter War reveals that Millennium Village Blog accused Clemens and Demombynes of hard hearts towards suffering (search the blog for "suffering"). UPDATE 2: FEB 8 4:30PM: concluding coverage by @PSIHealthyLives @viewfromthecave of the Great Twitter War prompted by this post between @aidwatch and @earthinstitute, with collateral attacks on @m_clem, ending in a non-acceptance of debate by head of @earthinstitute.

UPDATE Feb 8 11:30am: sent comment with link to this post to DFID Independent Commission for Aid Impact. Spokesperson promptly responded, rejected my comment for consideration on technical grounds, but did warmly invite me to complete the anonymous online mass Survey Monkey. It probably doesn't mean much, unless the Independent Commission already learned the brilliant strategy of bureaucratizing the critics? I do feel a wee bit sorry for one of your Commisioners, the great John Githongo, who presumably did not risk his life so he could be reading anonymous results from Survey Monkey.

Nobody is more tired of the interminable Sachs-Easterly debate than one guy named Easterly...alas, I seem to be stuck in a kind of Critic Trap, in which the ideas criticized keep reappearing unchanged, requiring equally unchanged criticisms, keeping me in chronic peril of taking myself way too seriously.

So it was with great weariness I heard the news that the British aid agency DFID (otherwise probably the best bilateral aid agency) is close to financing a brand new Millennium Village in northern Ghana, near Bolgatanga. I had hoped for something better from the new UK government, which had seemed like an improvement over the Blair and Brown ("We know the answers, just double aid") team .

As it happened, I passed by the proposed MVP site last summer. The proposed villages are right on the main road in one of the most NGO-intensive places anywhere (see the sign below, in which NGOs apparently own the region).

The usual critique that selection bias of the Millennium Villages makes evaluation impossible may be somewhat relevant given the political realities that (1) the current government chose the villages for the MVP, (2) the incumbents have frequently promised to do more for the North, (3) the MVP came along and may be a high visibility way to keep that promise, and (4) ergo, the government will likely do everything possible to make the project succeed, showing nothing about scalability for thousands of villages elsewhere. In short, this new MV may be about as informative as my feeding my own children is informative on whether child nutrition programs work.

And how good is the track record of the MVP taking evaluation seriously? Michael Clemens and Gabriel Demombynes posted the following on the World Bank Africa blog last Friday:

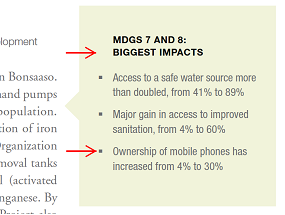

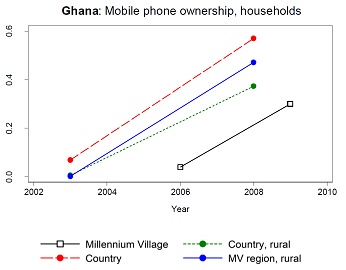

In a June 2010 report called Harvests of Development, the Project claimed that the impacts of the project included expanded cell phone ownership. For example, the MVP claimed that increases in cell phone ownership at the Ghana site were caused by the project, in this extract from page 91 of the MVP report:

This claim has little basis, because cell phone ownership has been expanding at about the same rate all around the MVP site in areas untouched by the project. ....

But on Tuesday, months after multiple discussions we’ve had with MVP leaders on our research, a post on the MVP’s blog restated the claim that the increase in mobile phone ownership at the intervention sites was caused by the Project...

{The Clemens and Demombynes paper does the same cell phone analysis with the same results in the MV of Sauri, Kenya.}

They were responding to a blog post on the MVP web site on February 2, 2011 as follows:

Sauri looks back on five years of success

Infrastructure: ... The proportion of households owning a mobile phone has increased four-fold....

In short, independent observers made an irrefutable argument that a claim was invalid, the MVP heard the argument, seemed to accept it, and then repeated the previous claim unchanged.

Or in other words, if nobody is listening to any evaluations anyway, if I am bored and I am boring everyone else, why should I want to be Official Sachs Critic any longer?

Messrs. Clemens and Demombynes, you may want to check out a new job opening...

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality