More Tales of Two Tails

The following post is by Dennis Whittle, co-founder of GlobalGiving. Dennis blogs at Pulling for the Underdog.

An eloquent 3 year-old would have been better asking "What the dickens are you talking about? Who is defining success? Who says failure is bad, anyway?" - Joe

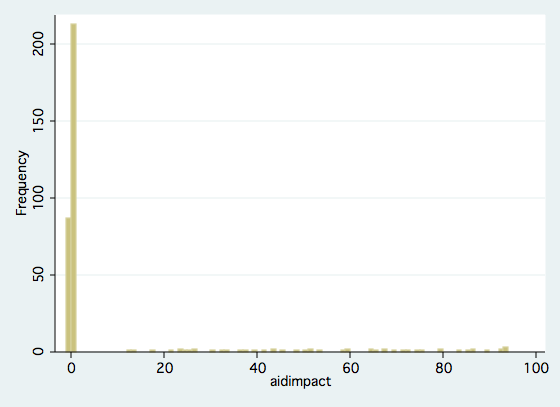

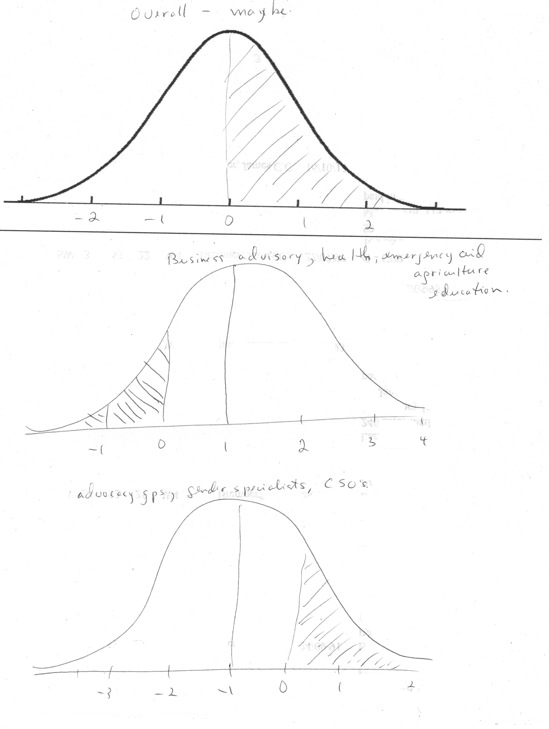

Earlier I blogged about aid cheerleaders and critics. Each camp argues about the mean outcome of aid rather than the distribution of impact among projects. Both camps agree that some projects have positive results and others negative. So why not try to figure out which projects work and focus our resources on them?

I got some great and insightful comments and a few nice aid distribution graphs from readers. Here are some key themes:

- The mean *does* matter if the distribution is random. In other words, if we can't predict in advance what types of projects will succeed, we should only spend more resources if the mean outcome is positive.

- Many people believe that on average the biggest positive returns come from investment in health projects.

- We should also look at the distribution of impact even within successful projects, because even projects that are successful on average can have negative impacts on poorer or more vulnerable people.

- Given the difficulty in predicting ex-ante what will work, a lot of experimentation is necessary. But do we believe that existing evaluation systems provide the feedback loops necessary to shift aid resources toward successful initiatives?

- "Joe," the commenter above, argues that in any case traditional evaluators (aid experts) are not in the best position to decide what works and what doesn't.

Petr Jansky sent a paper he is working on with colleagues at Oxford about cocoa farmers in Ghana. The local trade association was upset that they could not get pervasive adoption of a new package of fertilizer and other inputs designed to increase yields. According to their models, the benefits to farmers should be very high. The study found that - on average - that was true, but that the package of inputs has negative returns to farmers with certain types of soil or other constraints. Farmers with zero or negative returns were simply opting out.

At first glance, these findings seem obvious and trivial. But they are profound, in at least two ways. First, retention rates are an implicit and easily observable proxy for net returns to farmers. We don't need expensive outside evaluations to tell us whether the overall project is working or not. And second, permitting farmers to decide acknowledges differential impacts on different people even within a single project.

What other ways could we design aid projects to allow the beneficiaries themselves to evaluate the impact and opt in or out depending on the impact for them personally? And how would it change the life of aid workers if their projects were evaluated not by outside experts and formal analyses but by beneficiaries themselves speaking through the proxy of adoption?

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality