TransparencyGate: the end of the road

by Till Bruckner, PhD candidate at the University of Bristol and former Transparency International Georgia aid monitoring coordinator. Sixteen months after I first filed a Freedom of Information Act request with USAID for the budgets of American-financed NGO projects in Georgia, I have reached the end of the road. Rejecting my appeal, USAID has confirmed that it continues to regard NGO project budgets as “privileged or confidential” information, and will not release budgets without contractors’ permission.

The opacity of USAID’s subcontracting makes it impossible for researchers to get access to comprehensive and comparable data that could inform debates about the effectiveness of delivering aid through NGOs. For example, the issue of aid fragmentation within NGOs could only be raised because Oxfam GB voluntarily provided a researcher with a list of all its projects abroad.

USAID is on very thin ice when it tries to push developing country institutions to become more accountable. The next time USAID lectures an African official on the importance of transparency in public procurement, I hope she will pull out a list of blacked-out budgets and argue that her ministry is following American best practice when it treats all financial details of its subcontracting arrangements as “privileged or confidential.”

Financial opacity also remains the default position for most NGOs. CARE and Counterpart instructed USAID to release more information in response to this FOIA, and they deserve credit taking for this step. However, USAID’s latest information release suggests that no other NGO has given the green light for such information sharing.

The recent public statements by NGOs and other aid actors reveal wildly divergent understandings of what accountability should mean in practice. As InterAction points out, “the issue at hand is what constitutes relevant information, and to whom specific information should be disclosed.”

What information is relevant? Scott Gilmore argued that we should be interested in accountability for outcomes rather than for expenditures, and many commentators on this blog have questioned the desirability or utility of public access to NGOs’ salary figures or NICRA rates, and raised concerns about privacy, security and competitive disadvantages.

I continue to believe that project proposals, including uncensored budgets, are essential components of a meaningful rendering of account. Proposals spell out what an NGO plans to achieve, when, where, why and how, and at what cost. If we don’t even know what a project sets out to do, and with what resources, how can we hold it to account for its success or failure?

Equally, there is disagreement on who qualifies as a legitimate stakeholder. CNFA and Mercy Corps have both emphasized that they feel themselves obliged to render account to institutional donors and beneficiaries, but not necessarily to third parties. This line of argument glosses over the sad reality that NGOs do not reveal project budgets to their beneficiaries either. Also, as charities enjoy tax-exempt status and spend public money, we are all donors, like it or not. And we all care about the beneficiaries, so we are all “aid watchers”.

If project budgets are not particularly relevant, and scrutiny by ordinary citizens does not bolster accountability, why do international NGOs regularly make their local sub-grantees post project budgets in public places for all to see? As far as I know, no Northern NGO has worried that such excessive transparency may compromise the privacy, security or competitiveness of community-based NGOs in the South.

This FOIA journey has shown one thing above all: NGOs (save Oxfam GB) simply do not want outsiders to see their project budgets, full stop. Not a single NGO has used this forum to announce its willingness to give beneficiaries or other stakeholders access to its project proposals and budgets in the future, even though every country director has these documents on his hard drive and could attach them to an email within two minutes.

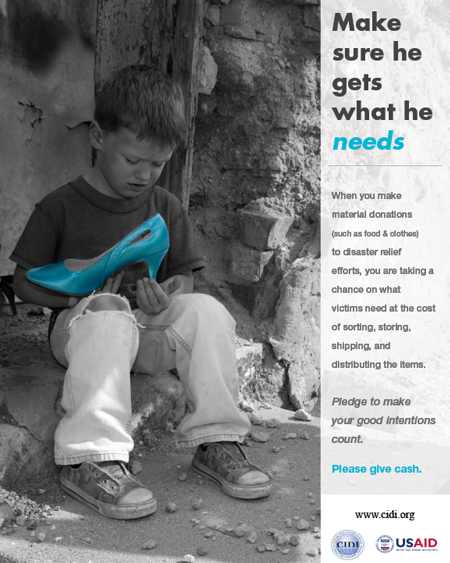

Project budgets are shown only to those stakeholders who have the power to force NGOs to open their books: donors, headquarters, and audit institutions. The poor and powerless have to be content with whatever information NGOs choose to provide.

Can NGOs be accountable without showing outsiders where the money goes? The Humanitarian Accountability Project thinks so. “Public disclosure of financial information is not a requirement for HAP membership,” HAP recently confirmed. InterAction concurs, stating that it “purposefully does not define in our standards specific mandates for disclosure.” InterAction also highlights “the request of some donors to keep their financial support private.”

Transparency International, drawing parallels to the oil and gas industry, strongly disagrees: “Competitive advantage or even privacy, are not acceptable exceptions. Only personal physical security suffices.” Aidinfo observes that “the burden of proof is shifting to those who would keep information secret.”

Donor-abetted secrecy jars with President Obama’s call at last week’s MDG summit: “Let’s resolve to put an end to hollow promises that are not kept. Let’s commit to the same transparency that we expect of others.”

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality