I read recently the First Law of Policy Economics: Every inefficiency is someone’s income.

US food aid policy is definitely no exception, and it is riddled with inefficiencies.

Exhibit A: This invitation from a coalition of big US shipping interests to an event in Washington today. At this event, USA Maritime will have tried to convince lawmakers and their staff that ancient and outdated US food aid legislation, which requires virtually all US food aid to be bought in-kind from the US, processed and bagged in the US, and shipped on US-flag ships to even the most far-flung destinations, should not be altered.

Let us leave aside for a moment that the report recommending favorable policies for the US shipping industry was bought and paid for by the US shipping industry and may not be the most objective or trustworthy source on the subject.

The main thrust of the shipping industry’s argument is that handling, processing and shipping food aid creates US jobs—13,127 of them to be exact—and boosts US industry, leading to this actual headline: “Food For Peace Program Produces More Than 870 Iowa Jobs.” If these policies were removed, they argue, it would be less profitable to operate a ship under the US flag, the US-flag fleet would shrink, and American jobs would be lost.

“Did you know,” reads the invitation, “that these programs have positive economic consequences for our economy at home?” The report tries to quantify one benefit of current US food aid policies, but (obviously) does not discuss the considerable costs of these policies to US tax payers, to the US’s reputation and credibility abroad, and most importantly to programs’ intended recipients—the millions of hungry and malnourished people fed by the world’s largest food aid donor every year.

The shipping industry’s arguments don’t hold water for many reasons. Here are two of the big ones:

First, assuming that you did want to subsidize the US Maritime industry, US food aid policies that create an overpriced, uncompetitive oligopoly are NOT a good way to do it. There are much cleaner, simpler and more effective ways to support US Maritime, such as direct payments to vessel owners. There is no reason to bundle shipping subsidies in with humanitarian aid other than the deeply cynical logic that it’s easier to rally public and Congressional support around money for starving children than around padding to the bottom line of multinational shipping conglomerates.

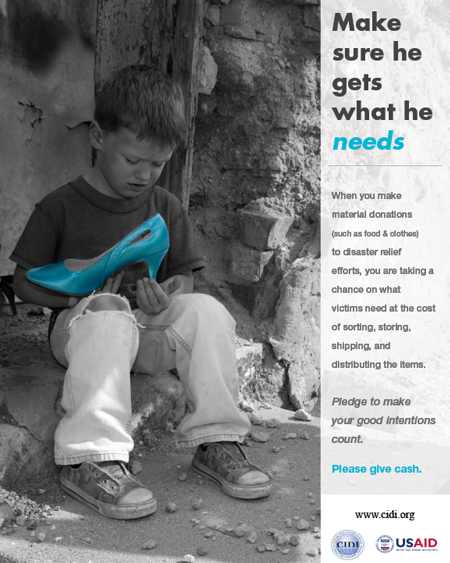

Second, current US food aid policies are NOT an effective or efficient way for the US to achieve what should rightly be the primary objective for food aid. According to the government’s own accountability office, buying food locally in sub-Saharan Africa (which is where the majority of US food aid goes) costs 34 percent less than shipping it from the US, AND gets there on average more than 100 days more quickly, AND is more likely to be the kind of food people are used to eating. I am not arguing that cash aid is ALWAYS better than food aid, only that any reasonable food aid policy would allow aid agencies the flexibility to determine what kind of assistance works best in each situation.

Despite resistance from all three sides of the iron triangle holding this legislation in place, innovators have managed to break loose about $400 million for pilot and supplemental programs over the last two years to buy food locally or regionally. This is still a small sum compared to the roughly $2 billion that the US spends annually, but it is progress.

With today’s lame report, the big shipping companies behind USA Maritime are asking us to value a few thousand American jobs in a declining and uncompetitive industry over America's humanitarian reputation abroad AND the lives of the millions more people around the world who would benefit from reform to US food aid policy.

Do we even have to say it? This is NOT a fair trade.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality