Worst in Aid: The Grand Prize

Hillary Clinton recently declared: “We are working to elevate development and integrate it more closely with defense and diplomacy in the field…The three Ds must be mutually reinforcing.” Clinton says that the 3D approach will elevate development to the level of diplomacy and defense. Unfortunately, it could instead lower development further to an instrument employed to achieve military or political priorities. Clinton foresaw these objections: “There is a concern that integrating development means diluting it or politicizing it – giving up our long-term development goals to achieve short-term objectives.” She said reassuringly, “[t]hat is not what we mean, nor what we will do.”

But it’s too late. Sacrificing long term development aims for short term military and diplomatic objectives is what the US already does, and the 3Ds is making it worse. That’s why the Grand Prize for the Worst in Aid goes to…the 3D approach, nominated by an anonymous reader.

References to the "3D approach,"… have become so pervasive in foreign policy, development, and national security circles that they have taken on the status of self-evident, common wisdom. - J. Brian Atwood, former USAID administrator, February 2010

The frequent contradiction between defense and development is the most obvious instance of 3D dissonance. A coalition of eight NGOs in Afghanistan lamented that “[d]evelopment projects implemented with military money or through military-dominated structres aim to achieve fast results but are often poorly executed, inappropriate, and do not have sufficient community involvement to make them sustainable.” Nonetheless, increasing amounts of aid get channeled through the military, “while efforts to address the underlying causes of poverty and repair the destruction wrought by three decades of conflict and disorder are being sidelined.”

An Oxfam case study on programs to reform the security sector in “frontline” states like Iraq illustrated another way in which narrow military goals (to train and equip soldiers and police) are not entirely compatible with development goals. The report found that an increasing reliance on military contractors rather than civilians “has strongly reinforced the focus on operational capacity over accountability to civilian authority and respect for human rights.”

In the battle of the Ds, enervated development loses to pumped-up defense, and not just in Afghanistan and Iraq. The trend goes two ways: USAID is compelled to spend more and more of its budget on states that are strategically and militarily important (The 2011 foreign aid budget allocates 20 percent of State and USAID money for “securing frontline states.”) A development priority like India (with a huge chunk of the world’s poor) loses out. At the same time, a growing proportion of what the US calls Official Development Assistance flows through the Pentagon rather than USAID.

Frequent readers of the blog will already be familiar with our final example. On Christmas Eve in Madagascar, President Obama bowed to the exigencies of diplomacy when he punished the nondemocratic government of Madagascar by taking away trade access to U.S. markets. But this same action was disastrous for development. Already, tens of thousands of jobs created textile exports to the United States under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) have been lost. Factories are closing, increased competition among street workers is pushing down wages, and the effects are spilling over into neighboring countries that made inputs to Madagascar’s factories. Any claim that the Madagascar AGOA delisting was part of a high-return Diplomatic initiative to promote Democracy became a wee bit more tenuous when we saw Angola, Cameroon, and Ethiopia named on Christmas Eve as still eligible for AGOA.

[We could go on -- This week brought another collision of development and defense/diplomatic goals in Somalia.]

The lie that underlies the 3D framework is that development, diplomacy, and defense are complementary (or totally “mutually reinforcing”); that there are no difficult choices to be made. Alas, politicians are fond of denying the existence of tradeoffs (we are not trying to pick on Hillary in particular; many politicians are guilty of this).

The only 3D strategy that makes sense for development is one that acknowledges the frequent conflicts between these three very different goals as natural outcomes of their different agendas. Then we can hold our politicians accountable when they sacrifice Development big-time to achieve small-time (or sometimes illusory) Diplomatic or Defense goals.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

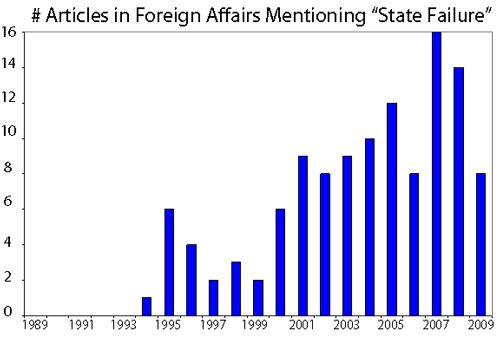

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.