Scratch and win for authentic malaria drugs

Here’s a problem most people in rich countries don’t often have to deal with: wondering whether the drugs you’ve just picked up from your local pharmacy will kill you, save your life, or give you just enough active ingredients to create a new drug-resistant strain of an otherwise curable disease. Counterfeiting does happen in rich countries, but more prevalently with “lifestyle drugs” like Viagra or allergy meds. Poor countries often have thriving counterfeit markets for drugs needed to combat more life-threatening diseases like malaria—for example in a recent study in Madagascar, Senegal and Uganda, between 26 and 44 percent of antimalarial drugs failed quality tests.

What if consumers could scratch off a panel on a drug package, send a text message containing that package’s unique 10-digit code, and get back a message that the drugs were authentic and safe to use, or fake? This is the idea behind mPedigree, a start-up led by Ghanaian social entrepreneur Bright Simons. According to a recent Bloomberg article mPedigree is planning a trial of their system using 125,000 packets of antimalarials in Ghana and Nigeria later this year. A rival service called Sproxil, started by another of mPedigree’s founders, Ashifi Gogo, is being deployed in Nigeria.

What if consumers could scratch off a panel on a drug package, send a text message containing that package’s unique 10-digit code, and get back a message that the drugs were authentic and safe to use, or fake? This is the idea behind mPedigree, a start-up led by Ghanaian social entrepreneur Bright Simons. According to a recent Bloomberg article mPedigree is planning a trial of their system using 125,000 packets of antimalarials in Ghana and Nigeria later this year. A rival service called Sproxil, started by another of mPedigree’s founders, Ashifi Gogo, is being deployed in Nigeria.

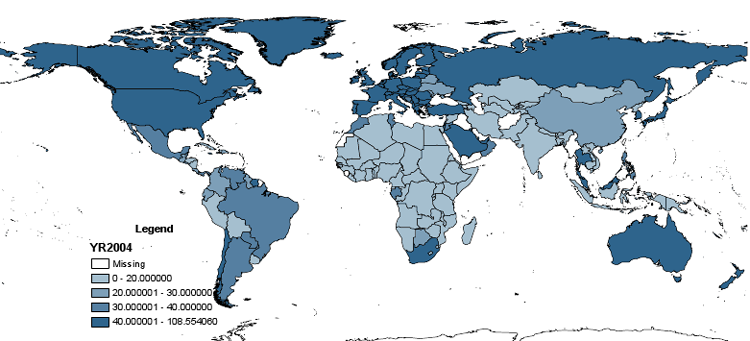

The idea’s brilliance lies in its reliance on two existing, affordable, and familiar technologies: the cell phone and the scratch card. Access to cell phones in Ghana and Africa as a whole has increased rapidly over the last decade, and scratch cards are a common way for people to top up their pre-paid cell phones.

The potential benefits are clear. From the perspective of the consumer, mPedigree is a quick, easy and cheap way to discover whether just-purchased drugs are real or fake. For drug makers, the new service will allow them to capture a greater share of the market as they drive out fakes and low-quality competitors.

On the other hand, this raises the question of who will be protected and who will be excluded if the services become widespread. If the idea spreads to drugs for which there are locally-made versions or legitimate generics available, will larger drug makers who use mPedigree be able to drive smaller firms who can’t afford it out of business? Or will mPedigree strive to include all the legitimate drug makers in the market?

mPedigree’s scratch and win panels are no permanent substitute for what’s missing in those markets where counterfeit antimalarials flourish—namely a well-functioning drug regulatory system, good consumer education about the danger of fakes, and a plentiful supply of effective antimalarials that are affordable and available to all who need them. But as a stopgap measure, they might be a winner.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality