An ongoing exhibition at NYU’s Casa Italiana introduces American audiences to a new Romantic hero, the Italian explorer and conquerer Pietro di Brazza. In three small but fascinating rooms of photographs, maps and drawings, the exhibit lays out the argument that Africa would have been better off with more of the kinder, gentler colonialism of Pietro di Brazza, and less of the harsh colonialism of Henry Stanley, the Anglo-American explorer in the service of the notorious most ruthless imperialist ever, King Leopold of Belgium.

Pietro Savorgnan di Brazza, photographed by Felix Nadar in Paris, around 1882

Born in Rome and educated in France, Pietro di Brazza joined the French Navy at the age of 18. His early expeditions, up the Ogoué river (now in Gabon) and across the Batéké plain (now part of Congo-Brazzaville), laid the groundwork for the French colonial empire in Equatorial Africa.

On his expeditions, he carried with him French flags and bestowed them on tribal leaders as symbols of protection against other predatory colonial powers. He signed a treaty of friendship with the leader of the powerful Batéké tribe, Makoko Iloo I, which would eventually cede much of what is now Congo-Brazzaville to French control. As a reward for his successful explorations, France made Brazza the Commissioner General of French West Africa, where he governed for 15 years.

Examining the allegiances, writings and portraits of the two explorers, the exhibit draws a studied contrast between the humanist ideals of Brazza, who opposed slavery and fought to prevent France from granting concessions to commercial merchants in Africa, and the mercenary tactics of Henry Stanley, whose exploration of Lake Victoria and the Congo River led the way for King Leopold to establish an empire of unprecedented brutality and exploitation in what is now the DRC.

Brazza was a man ahead of his time, the curators contend, who understood the need for sustainable development, and treated the natives with tolerance and respect. “I believe that the future of Western Africa and the Congo basin depends on the rich indigenous culture and trade—not on colonization through European immigration,” he said in a speech to his admirers in Paris.

Still, the exhibit left us wondering: Do we really need a colonialist hero? Is the world short on idealized portraits of rugged white men in native gear, posing against romantic backdrops of sand and mountains? For all Brazza’s noble ideals, should we pass lightly over the fact that he was in fact the colonial governor of French Congo and Gabon? That his “gift” of Congo and Gabon to the Republic of France opened the door to decades of war and commercial exploitation? That his presence in the Congo robbed its inhabitants of their right to self-rule?

After all, Brazza could not control the massive tide of history that his explorations and his friendship treaty with the Batéké leader set in motion. He himself fell out of favor with the French government, was dismissed from his post, and died in Algiers a disillusioned man. His last report, decrying the abuses of power in the French West Africa that followed from evidence of Leopold’s enormous profits in the rubber trade, was suppressed and has still never been released.

Brazza may have truly believed that the French flags he gave to the tribal chiefs were peaceful offerings of protection, symbols of liberté, egalité, and fraternité. But from our vantage point today it’s hard to see them other than as the symbols of colonial domination that, in very real, enduring terms, they were.

True, some colonial empires were better than others. Some colonial rulers were more benevolent than others. But colonialism, stripped of all its “White Man’s Burden” justifications, is at its core a kind of violence. And any historian who ignores this is engaged in hagiography, not history.

You can still catch “Brazza in Congo: A Life and Legacy” which runs through April 17 at NYU’s Casa Italiana. You can also see a mural created by the Brazzaville artists from the Poto-Poto School of Painting to commemorate the meeting between Brazza and Makoko Iloo I, at the National Arts Club.

The law firm Klayme, Chaise, & Steele LLC announced today that one of their clients was suing the prominent non-governmental organization (NGO) Care for the Children (CFTC) for unauthorized use of the client’s photo as a child..

The lawyers revealed their client is now a sophomore at a university, but refuses to give his name or home country to protect what is left of his privacy. The client remembers vividly the day he came across the cover of the CFTC brochure “Give for the Sake of the Children”, which featured a picture of himself as a child. The lawyers said, “At no time was permission given to CFTC by the child, his parents, or legal guardians to take such a photo, much less to broadcast innumerable copies of it around the Western world to gather funding for this organization.”

The law firm Klayme, Chaise, & Steele LLC announced today that one of their clients was suing the prominent non-governmental organization (NGO) Care for the Children (CFTC) for unauthorized use of the client’s photo as a child..

The lawyers revealed their client is now a sophomore at a university, but refuses to give his name or home country to protect what is left of his privacy. The client remembers vividly the day he came across the cover of the CFTC brochure “Give for the Sake of the Children”, which featured a picture of himself as a child. The lawyers said, “At no time was permission given to CFTC by the child, his parents, or legal guardians to take such a photo, much less to broadcast innumerable copies of it around the Western world to gather funding for this organization.” From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

Here’s another discussion relevant to the earlier post that

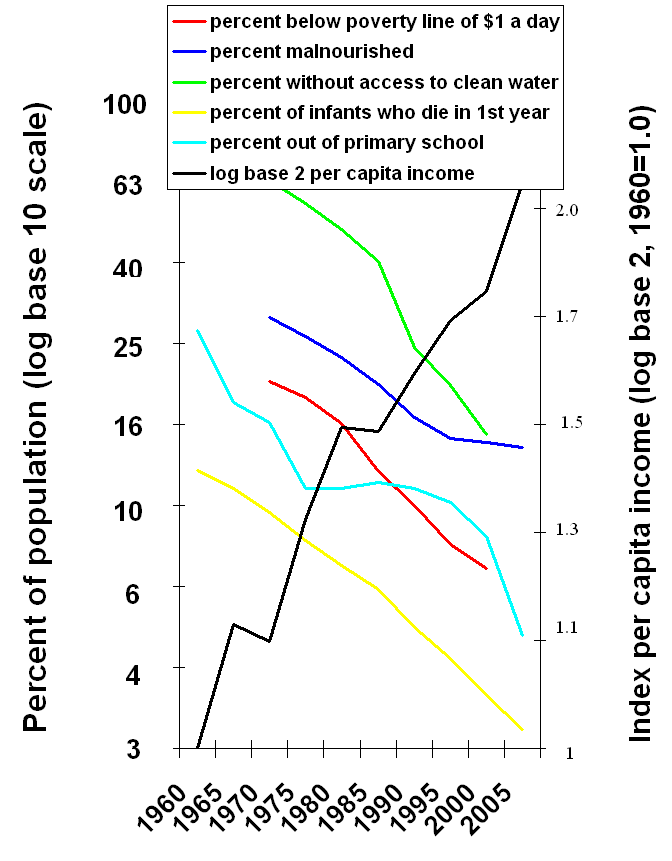

Here’s another discussion relevant to the earlier post that  Use a precise definition of poverty: living on less than $1.25 a day, adjusted for purchasing power. Give the precise number who fit that definition.

Use a precise definition of poverty: living on less than $1.25 a day, adjusted for purchasing power. Give the precise number who fit that definition.

Display pictures of poor children (alternatively women).

Display pictures of poor children (alternatively women).

Senegalese entrepreneur Magatte Wade on the

Senegalese entrepreneur Magatte Wade on the  (Mother’s Day Edition)

(Mother’s Day Edition)