The Food’s Not Much, But the Lavatories Are Fabulous

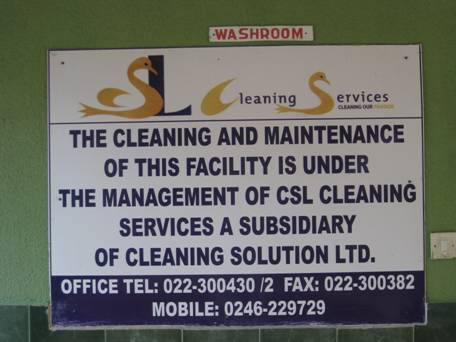

I was startled during a meal at a non-luxury restaurant out in the boondocks in Ghana when my Ghanaian hostess suggested I check out the bathrooms. Lo and behold, they were indeed incredibly clean and hygienic. The reason seemed to be given by the following sign outside the lavatory.

Apparently this private firm had won a lot of bathroom-cleaning contracts as a way to promote its own cleaning products for the homes of the Ghanaian middle class (I wish some entrepreneur in the US would think of this for our disgusting gas station bathrooms).

I was startled during a meal at a non-luxury restaurant out in the boondocks in Ghana when my Ghanaian hostess suggested I check out the bathrooms. Lo and behold, they were indeed incredibly clean and hygienic. The reason seemed to be given by the following sign outside the lavatory.

Apparently this private firm had won a lot of bathroom-cleaning contracts as a way to promote its own cleaning products for the homes of the Ghanaian middle class (I wish some entrepreneur in the US would think of this for our disgusting gas station bathrooms).

Now I’m not going to take a cheap shot and say this demonstrates the superiority of the private market to solve problems – especially when the private sector restaurant we were eating at was unable to supply most of the dishes that were listed on the menu (although those dishes that were available were fine). Maybe it’s a symptom of the information problems of a poor economy that the free market does well at supplying some goods (the frequently cited but still amazing penetration of cell phones and the internet into Ghana is another one), but misses out on others.

Of course, the “aid economy” is still much worse. Lacking any market or democratic mechanism to get feedback from the customers on what they want, there are even more extreme disparities between hits and misses on aid-supplied goods. One lightly used aid-financed road is a 4-lane highway in perfect condition, while the major Accra to Kumasi thoroughfare is a two-lane road riddled with potholes. Aid-financed buildings are always abundant, but some of the little things that make the buildings fully functional are missing. I saw a health clinic that was missing beds for the patients and tables for the nurse to work on (which was still much better than the well-documented problem of health clinics lacking medicines or health workers). The nurse’s solution was inventive – she kept moving one bed back and forth between the maternity ward, the post-natal recovery room, and the regular patient room, and she hijacked a table from the local aid-financed kindergarten. I am reminded of the old Soviet factory managers that creatively adapted to the perennial shortages in a centrally planned economy – much like the chronic shortages in an aid-financed economy.

It goes on. Food storage rooms are missing enough pallets to keep the food off the floor so it doesn’t rot. Some villages got a mass bed net distribution two years ago, but now some nets are torn, have been washed too many times because the village is so dusty, or some villagers missed getting nets altogether because they were absent on bed net distribution day. Moreover, the bed net villagers in an informal chat indicated other needs that seemed even more pressing to them than nets – they lack any reliable form of transport – to the capital, Accra, which is vital to them for business. Their only hope is to wait hours and hours by the road for some form of transport to come along. And more than anything they wanted – guess what – clean lavatories. There was not a single functioning lavatory in the village, and the villagers seemed well aware of the adverse health consequences of not having lavatories.

This is not to take away from the valiant aid efforts that did supply some critical goods, but it is clear the aid economy is a non-market system that has the same chaotic mixture of over-supply of some goods and shortages of others, common to other non-market systems. As the restaurant example above indicates, however, the free market is also uneven in supplying goods in poor economies. The difference is that we know in the long run, from the historical experiences of other countries, markets get more reliable and get wider and deeper coverage as a country develops (i.e. as transaction and information costs fall, and as markets get thicker with rising consumer demand). And for public goods, increasingly democratic systems with an active citizenry demanding services from their government create a kind of “political market” for public goods that does eventually succeed in creating better and more public services.

Unfortunately, history equally suggests that the non-market systems like the aid economy never do resolve their allocation problems of feast-or-famine. Aid may be a short-term expedient for some critical needs, but already in Ghana far more people are getting their needs met through private markets. Every visitor to Ghana or any other poor society has to be struck by the amazing number and diversity of small producers and retailers visible at every turn of the road – the “Royal Metal Works,” the “God is Able Provisions Store,” the “Urban Fashion and Business Center,” or the simple bald advertisement “Cement is Sold Here.” There is a lot more hope for the villagers and urbanites of Ghana from improved functioning of markets and of democratically-accountable public services than from the aid system. I’m willing to bet that the market will eventually compel the restaurant with the clean lavatories to have most of the items on the menu.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality