Stop panicking: Capitalism repeatedly recovers from financial crises

UPDATE 2 (3/24, 12:59PM EDT) Tyler Cowen is almost convinced (see end of this post) UPDATE (3/23, 2:30 EDT): see GREAT responses by Ross Levine and Mark Thoma at the end of this post

I am just beginning to dive into the awesome book by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Along with great analysis, they have some wonderful pictures, evidence, and data. What I say here is my own take on it.

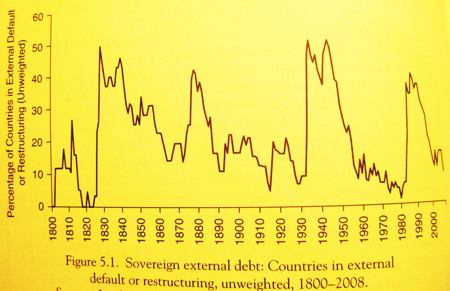

First, financial crises are remarkably common. Their Figure 5.1 shows the number of countries that have defaulted on their external debt (one possible dimension of a financial crisis) over the last two centuries. The numbers come in episodic waves of defaults and involve a remarkably high number of countries in each wave:

Second, the global capitalist system does well in the long run anyway. Average per capita income in the world (a shaky estimate, but probably right order of magnitude) increased by a multiple of 12 over 1800-2008, despite repeated epidemics of financial crises.

The US is arguably the country with democratic capitalism the longest, and it also shows a steady upward trend from 1870 to the present, despite repeated banking crises (using those identified by Reinhart and Rogoff), with usually little effect of each crisis on output relative to trend (except for the Great Depression).

I don’t mean to minimize the short run pain that the current financial crisis has caused. It’s horrible. But there is no reason to panic about the long run growth potential looking forward.

The obvious rejoinder is Keynes’ “in the long run, we are all dead.” But we can’t ignore that Capitalism already survived repeated financial crises and has made us all vastly better off despite them. So here’s a counter-quote: “In the long run, we are all better off because our dead ancestors stuck with capitalism.”

UPDATE (3/23, 2:30PM EDT) Ross Levine, the scholar whom I trust most about addressing financial crises, sent me the following comment by email when I asked him his opinion:

This is a great summary! I would, however, point out that this crisis could be different, depending on your view of the adaptability and elasticity of institutions. In particular, this crisis, including the build-up and the resolution, involved a massive redistribution of wealth to the very wealthy. It also involved an unprecedented decline in market discipline through government policy. Thus, from my perspective, to get the Reinhart and Rogoff result over the next decade or so, this must involve an institutional adjustment to correct the distorted incentives that currently exist. What are the forces that lead to this type of adjustment in some economies and not in others?

Mark Thoma, on his great blog Economist's View, responded to my request for a comment. A summary (see his post for his full response):

My take is a bit different. The graph of per capita income from 1870 - 2008 seems to say we shouldn't worry that aggressive intervention to stimulate the economy will cause long-run problems. It may help substantially in the short-run, but the graph above indicates it's unlikely to have long-run consequences. So, I agree, let's not panic. Let's not panic and start reducing stimulus measures too soon, or be too timid with stimulative policies, out of fear it might harm long-run growth.

....

Finally, on the general "stop panicking" message, when people are hurting -- and they are -- we ought to panic. Legislators have given little indication that the understand the urgency of the employment problem we face. We need more panic, not less, about the employment situation.

UPDATE 2: Tyler Cowen on a view he "toys with but does not (yet?) hold":

Financial panics and economic crises are nearly inevitable...

More and more, people will turn to the wisdom of the great 19th century economists on financial panics, bank runs, and the like. It was an intellectual mistake to think we had ever left that world for good.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality