Eternal sunshine of the useless charts

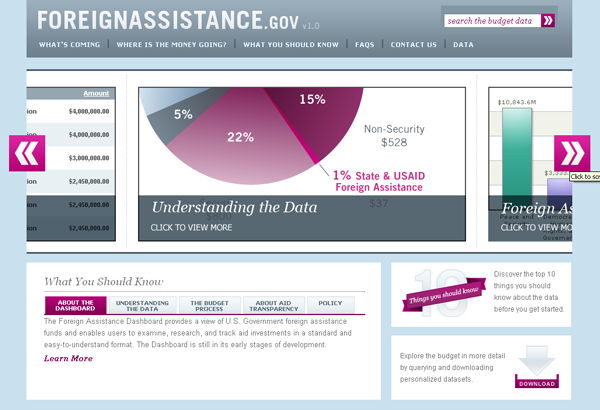

After all the blogging we’ve done on how hard it is to find complete and accurate information (as opposed to “success stories”) on USAID’s website, I think we’d be remiss not to mention a new US government site launched just before the holidays. The Foreign Assistance Dashboard is the first version of a site that will someday allow users to create charts and tables showing where and how well US aid funds have been spent.

On the plus side, it looks good, makes pretty charts, and it’s easy to use. In future iterations, US officials have said that it will publish data in an internationally comparable format. (This is important so that recipient countries, which receive aid from so many different donors, can get a full picture of aid inflows.)

The page on Pakistan tells us, for example, that $3 billion has been requested from Congress for Pakistan in 2011; $1.6 billion of that is for “Peace and Security,” and most of that is specifically for “Stabilization Operations and Security Sector Reform.”

On the minus side, it’s missing most of the information that actually matters to anyone tracking where the money goes and measuring its impact. The country information pages are incomplete because they exclude funds allocated to regional offices rather than country offices. And, as you can see from the below chart, the site has only data from USAID and State, and only shows appropriated amounts, not what has actually been spent.

While I admire the guts it took to publish such an aspirational matrix, I fear the day may still be far away when we will see a nice row of Xs in that last performance data column. Still, a recent editorial from transparency guru Owen Barder reminds why that is a goal worth pushing for:

While I admire the guts it took to publish such an aspirational matrix, I fear the day may still be far away when we will see a nice row of Xs in that last performance data column. Still, a recent editorial from transparency guru Owen Barder reminds why that is a goal worth pushing for:

The shift to a global information standard for aid sounds a rather dull and technocratic change, but a common standard for sharing information unlocks a world of possibility. It will enable the information from multiple aid agencies to be easily used by governments, parliaments and citizens in donor and developing nations.

It democratises aid, removing the monopoly of information and power from governments and aid professionals. It inspires innovation and informs learning. It reduces bureaucracy. It also makes it possible for communities to collaborate, for citizens to hold governments to account and for the beneficiaries of aid to speak for themselves.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality