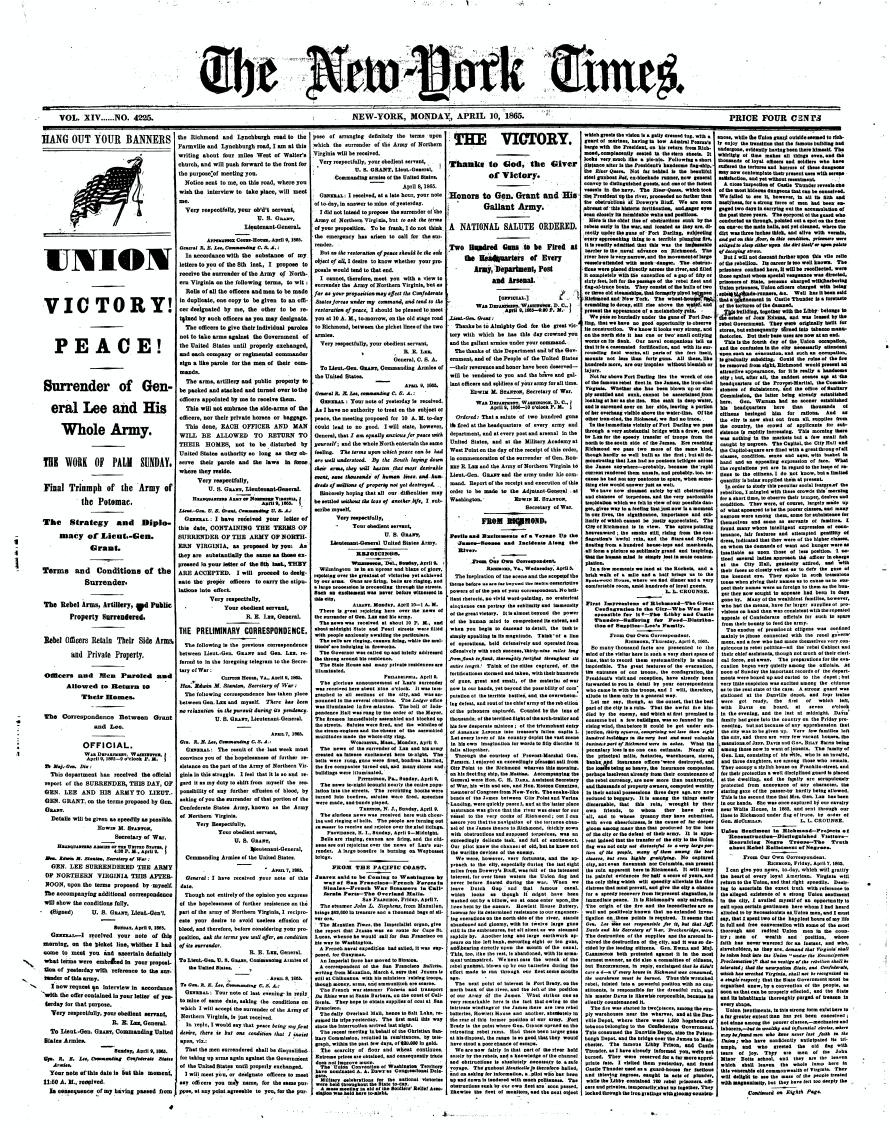

Development Social Science in medical journals: diagnosis is caveat emptor

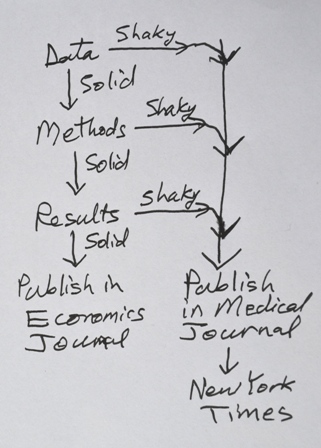

Aid Watch has complained before about shaky social science analysis or shaky numbers published in medical journals, which were then featured in major news stories. We questioned creative data on stillbirths, a study on health aid, and another on maternal mortality.

Aid Watch has complained before about shaky social science analysis or shaky numbers published in medical journals, which were then featured in major news stories. We questioned creative data on stillbirths, a study on health aid, and another on maternal mortality.

Just this week, yet another medical journal article got headlines for giving us the number of women raped in the DR Congo (standard headline: a rape a minute). The study applied country-wide a 2007 estimate of the rate of sexual violence in a small sample (of unknown and undiscussed bias). It did this using female population by province and age-cohort -- in a country whose last census was in 1984. (Also see Jina Moore on this study.)

We are starting to wonder, why does dubious social science keep showing up in medical journals?

The medical journals may not have as much capacity to catch flaws in social science as in medicine. They may desire to advocate for more action on tragic social problems. The news media understably assume the medical journals ARE vetting the research.

We could go on and on with examples. The British Medical Journal published a study of mortality of age cohorts in five year bands for both men and women from birth to age 95 for 126 countries—an improbably detailed dataset. (The article was searching through all the age groups to see if any group's mortality was related to income inequality.). Malaria Journal published a study of nationwide decreases in malaria deaths in Rwanda and Ethiopia, except that the study itself admitted that its methods were not reliable to measure nationwide decreases (a small caveat left out later when Bill and Melinda Gates cited the study as progress of their malaria efforts).

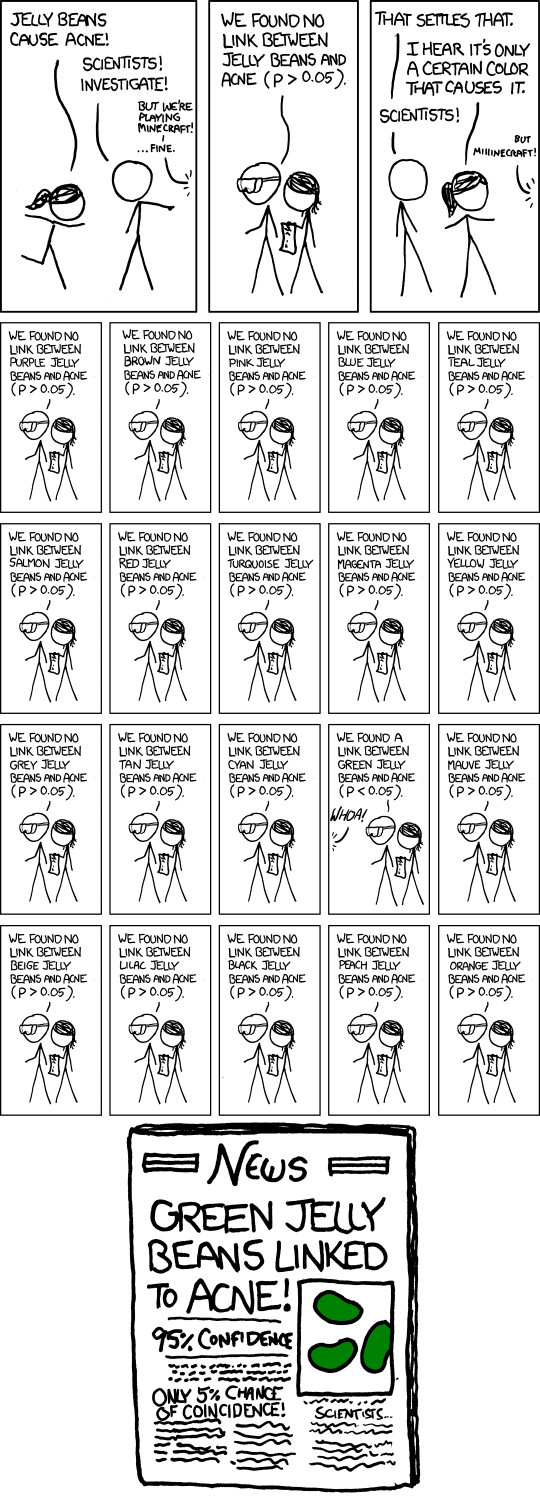

The Lancet published a study that tested an “Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE)” in order “to assess a structural intervention that combined a microfinance programme with a gender and HIV training curriculum.” The conclusion: “This study provides encouraging evidence that a combined microfinance and training intervention can have health and social benefits.” This was a low bar for "encouraging:" only 3 out of the 31 statistical tests run in the paper demonstrate any effects -- when 1 out of every 20 independent tests of this kind show an effect by pure chance. (The Lancet was also the culprit in a couple of the links in the first paragraph.) Economics journals are hardly foolproof, but it's hard to imagine research like this getting published in them.

Medical journals would presumably not tolerate shaky medical science in the name of advocacy; why in social science? We also care about rape, and stillbirths, and dying in childbirth. That's why we also care about the quality of social science applied to these tragic problems.

Postscript: we are grateful to Anne Case and Angus Deaton for suggestions and comments on this article, while not attributing to them any of the views expressed here.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

From the brilliant

From the brilliant