Speech delivered at Harvard Faculty Club at Boston Global Forum, November 3, 2025

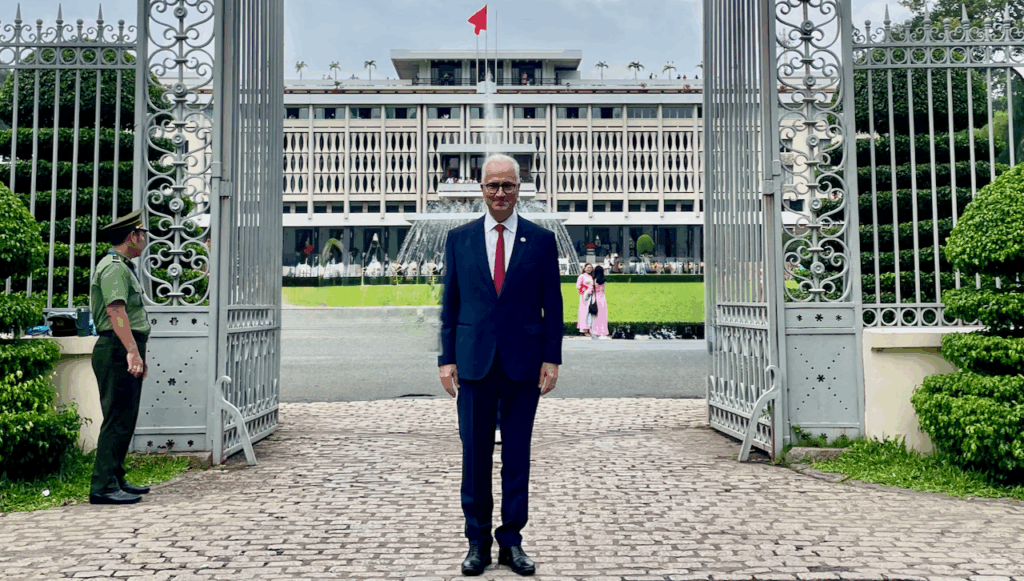

Photo: Kennedy in front of Independence Palace (formerly South Vietnam presidents’ house in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) in 2024.

I grew up in Pequot Lakes, Minnesota, a small resort town surrounded by our state’s “10,000 lakes.” Life there seemed far from world affairs—until one Fourth of July, when anti-war protestors took over nearby downtown Nisswa. The Vietnam War had reached even the quiet heart of America.

My parents hadn’t traveled far, but they wanted us to know the world. They bought an encyclopedia and subscribed to a National Geographic Weekly Reader. Through those pages I discovered distant lands. Suddenly one of them, Vietnam, erupted into my childhood.

My older cousin Charlie fought there. I remember him wearing his Army boots at the lake—boots that said more than words could about the burden his generation carried.

Years later, as a member of Congress, I flew home from visiting a Hmong refugee camp in Thailand. Our flight crossed over Vietnam, and I looked down at the endless green canopy, imagining Charlie fighting beneath it.

Decades later, I returned as a father, visiting my son aboard the USS Ronald Reagan, then docked at Da Nang. Standing on those beaches, I thought again of Charlie’s boots—and of how far our two nations had come.

The ship’s name was fitting. In 1980 Reagan observed of the Vietnam War, “It’s time we recognized that ours was in truth a noble cause.” He may not have realized how prophetic those words would become. For America’s stand—costly as it was—helped blunt China’s export of revolution and the Soviet arming of insurgencies, giving fragile democracies in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Taiwan, and South Korea time to endure. It also shaped the resolve within Vietnam to emerge self-reliant and free to choose its own course.

History will long debate whether the same result could have come without America’s stand. I doubt it. The U.S. did not win the war, but its commitment altered the region’s course, spurred the creation of ASEAN, and signaled that free nations need not yield the field to Chinese coercion. The Southeast Asia we see today—independent, confident, and increasingly prosperous—was built on the time and space America’s stand created.

The normalization of relations in 1995, announced by President Bill Clinton was one of history’s great acts of reconciliation. Vietnam’s Đổi Mới reforms and entry into ASEAN that same year achieved through diplomacy what decades of conflict could not—an open, independent, regionally integrated Vietnam. The dominoes once feared to fall instead stood back up, choosing cooperation over confrontation.

If the motive then was healing, the motive today is resilience—helping partners remain strong, sovereign, and secure in their independence.

Our core allies—Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and Taiwan—form the shield that deters aggression. But the neutral middle—Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore—will shape the region’s future. If these nations stay open, independent, confident, and focused on creating norms that make cooperation fair and freedom secure, the Indo-Pacific will remain balanced and free.

That is why Vietnam’s independence and ASEAN centrality matters. Strong allies keep the peace, but trusted partners sustain it—and together they must shape the rules that make peace last.

Two efforts are essential to that goal.

First, Vietnam preserving technological sovereignty. In a digital world, freedom depends on who builds your networks and writes your code. Chinese companies bound by Beijing’s cyber laws are not private actors but instruments of Chinese state control. That is why the work of the Boston Global Forum like our recent briefing of Vietnam’s leader To Lam in London and the many other works chronicled by Tuan and Professor Patterson in their book “The AI World Society: A 30-Year U.S.–Vietnam Partnership from Nha Trang to Boston” is so vital.

Second, ensuring economic independence. Recent tariffs, especially higher rates on Chinese transshipments, are a blunt stick to curb the region’s economic dependence on China. But Vietnam and ASEAN also need a carrot—trade arrangements and investments from the United States that enable economic diversification.

When I visited Hanoi with Tuan, a typhoon cut the trip short, but two places remain on my list: St. Joseph’s Cathedral, where I hope to pray for peace, and the War Memorial, to better understand how Vietnam remembers the conflict that shaped us both.

Yesterday was All Souls’ Day. I dedicate these remarks to all souls—American and Vietnamese—who gave their lives, and to all who turned pain into progress.

From the lakes of Minnesota to the beaches of Da Nang, from Nha Trang to Boston, ours is a story of reconciliation made real—of former enemies becoming enduring partners.

The true measure of history is not the wars we win, but the peace we sustain—and the future we build together.

Author

Mark Kennedy

Director & Senior Fellow