A Strategic Evaluation of the 2025 NSS

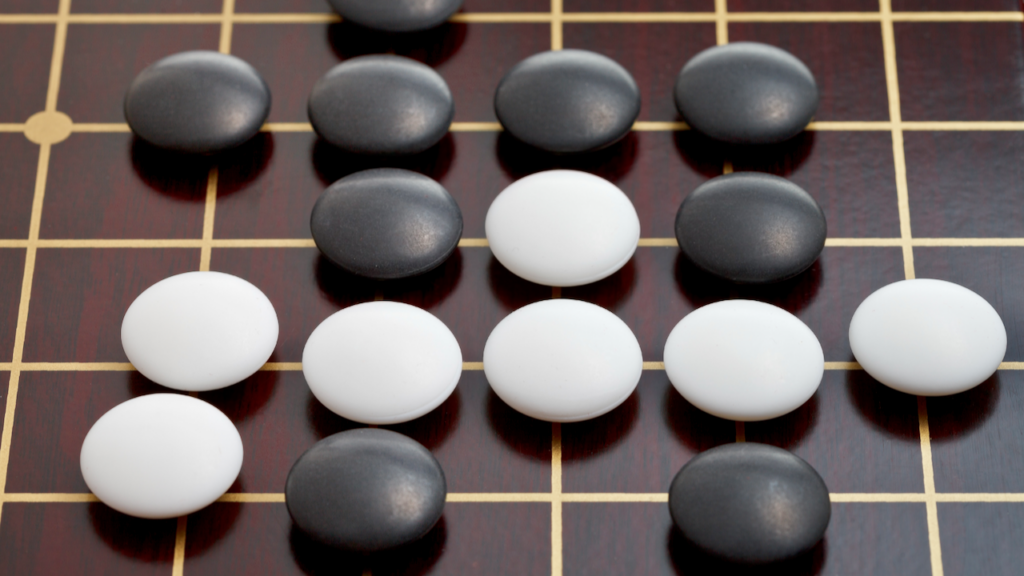

When I first studied wéiqí—the ancient Chinese board game known in the West as Go—I was struck by how different its logic is from chess. There is no king to capture, no decisive checkmate. The winner is the player who, over time, quietly shapes the board, surrounds more territory, and leaves the opponent with fewer safe options.

China’s leaders grew up in a culture that reveres wéiqí. As America adjusts its National Security Strategy (NSS) under President Trump, it is worth asking: if Beijing is playing wéiqí, what game is Washington now playing? And does the new NSS strengthen America’s position on the global board—or create new vulnerabilities in the name of short-term advantage?

What Wéiqí Teaches About Power

Wéiqí is a game of encirclement, not annihilation. Players place black and white stones on a 19×19 grid. The goals are simple to state but difficult to master:

- Secure more territory than your opponent.

- Surround rather than smash.

- Sacrifice locally to gain influence globally.

- Build strong, connected shapes—your own “alliances” on the board.

The best players avoid noisy, impulsive attacks. They play moves whose full purpose may only become clear many turns later. They strengthen their own positions even as they constrain the opponent’s. They never forget that the game is decided at the scale of the whole board, not a single fight in the corner.

With that lens, how does the new NSS look?

The Trump Corollary: Claiming a Hemisphere as Moyo

One striking feature of the NSS is the attempt to redraw America’s primary sphere of focus. The document announces a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine and calls for restoring American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere—economically, militarily, and politically.

On a wéiqí board, that is moyo-building: staking a large area of potential influence early, then backing it with stones that make it real. Reorienting more military presence, diplomatic energy, and industrial supply chains to our own hemisphere could, if executed well, strengthen America’s core position. It answers a legitimate concern that China and other competitors have made inroads in Latin America and the Caribbean while Washington was distracted elsewhere.

That part of the strategy is recognizably wéiqí-like. It seeks to secure a large, contiguous zone where American influence is dense and resilient. It is a reminder that sometimes the best way to compete abroad is to shore up the neighborhood that anchors your long-term strength.

The question, however, is what we are giving up to do so—and whether we are strengthening our own “stones” elsewhere on the board or weakening them.

Europe: Undermining Your Own Wall

Nowhere does the NSS diverge more sharply from wéiqí logic than in its treatment of Europe. The document describes the continent as facing “civilizational erasure,” warns that certain NATO members may become “majority non-European,” and calls for “cultivating resistance” to Europe’s current trajectory from within European nations.

In wéiqí terms, Europe has long been one of America’s strongest shapes on the board—a thick wall of like-minded democracies that amplified U.S. power and values. To broadcast that these allies are feeble, misguided, or culturally lost is not simply colorful rhetoric; it is the equivalent of poking holes in your own defensive formation.

A wéiqí player may attack an opponent’s weak group to gain strength. But you never casually invite instability in the very stones that protect your flanks. By publicly embracing Europe’s most polarizing factions and questioning whether future European societies will be “reliable allies,” the NSS flirts with turning our strongest wall into a contested zone.

If China is looking at the global board, it sees something it has not enjoyed in decades: a U.S. strategy document that reserves some of its sharpest language not for Beijing or Moscow, but for Brussels, Berlin, and Paris. That is not wéiqí. That is self-atari—putting your own stones at risk.

Russia and China: Playing Light Where the Threat Is Heavy

The NSS is notably restrained in its treatment of Russia. It emphasizes an “expeditious cessation of hostilities” in Ukraine to restore “strategic stability with Russia,” but says little about Moscow as a revisionist power.

In wéiqí, a dangerous group deep in your territory must be handled carefully. You may not attack it head-on, but you do not pretend it is harmless. You surround it, limit its eyes, and ensure it cannot expand. The NSS, by contrast, risks signaling that Washington is eager to normalize with Moscow even as Europe still faces an ongoing war on its soil. That will be read not just in Kyiv, but in capitals across Asia that are counting on sustained American resolve.

On China, the document is sharper economically—criticizing predatory practices, supply-chain leverage, and intellectual property theft—yet more restrained rhetorically on security, particularly around Taiwan.

Here again there is a wéiqí instinct: focus on reshaping the underlying economic terrain rather than telegraphing war. But wéiqí also demands that you pay close attention to the opponent’s thickest frameworks—China’s industrial policy, digital corridors, and infrastructure networks across the Global South. The NSS talks about reindustrialization and energy dominance at home, which are essential, but gives less attention to the alliance-based architectures abroad—standards, finance vehicles, digital rules—that will determine who actually controls the board in Africa, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

A wéiqí player who only looks at his own territory and not at the opponent’s expanding influence wakes up late in the game to discover he has been quietly surrounded.

Allies as Stones, Not Pawns

If you view the world through a wéiqí lens, alliances are not favors; they are stones that, if properly placed and connected, transform local strength into global advantage. The NSS rightly presses allies to spend more on defense and shoulder greater regional burdens.

That is a long-overdue rebalancing.

But wéiqí also teaches that stones must feel secure enough to play boldly in support of your strategy. If they believe they may be sacrificed without warning, they pull back, play timidly, or seek their own arrangements.

Encouraging Japan, South Korea, Australia, and others to invest more in deterrence, particularly along the First Island Chain, is good wéiqí.

Doing it while simultaneously sowing doubt in European capitals about America’s long-term partnership is not. The board does not reward a strategy that thickens shape in one area by weakening it somewhere else, especially when your primary competitor is playing across all quadrants at once.

Strength, Quietly Held

The NSS makes much of “America First,” sovereignty, and the end of the United States “propping up the entire world order like Atlas.” It is unapologetic about restoring American industrial capacity, energy production, and border control. Those are legitimate concerns for any great power and, if approached wisely, can enhance resilience.

But wéiqí rewards strength that is quietly held. The most effective moves are those that expand your options while constraining the opponent’s, without forcing them into an immediate corner. A strategy that is broadcast in harsh, ideological terms may solidify support at home, yet it also alerts competitors to your intentions and gives them more time to prepare counter-moves.

China’s wéiqí-inspired approach has often been to build influence through ports, cables, 5G networks, financing, and standards—stones that seem modest at first but over time create a web of dependency. When America replies with a strategy that loudly questions the legitimacy of some of its closest allies, downplays one of its chief military adversaries, and emphasizes transactional leverage in its own hemisphere, it risks playing a louder game on a quieter board.

How to Play a Stronger Game

If we took wéiqí seriously as a guide for strategic competition, a few adjustments to the NSS logic suggest themselves:

- Strengthen, don’t fray, your existing walls. Press Europe hard on defense spending and industrial renewal, but do so as a partner seeking shared strength, not as an outside agitator cultivating internal resistance.

- Make hemisphere strategy the base, not the ceiling. Reasserting presence in the Western Hemisphere is sound—if it is a foundation for global reach, not an excuse to accept encirclement elsewhere.

- Treat the Global South as contested territory, not just a resource pool. Infrastructure, digital standards, and capital access in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America are where many of the decisive points of this century’s game will be scored.

- Invest in alliance architecture, not just alliance rhetoric. Formal and informal “clubs” around semiconductors, AI safety, digital norms, and supply-chain resilience are the modern equivalent of connected stones that cannot be cut apart.

In wéiqí, it is possible to recover from a weak opening or a misjudged fight. But it is hard to recover from a failure to see the whole board.

America’s new National Security Strategy makes clear that we understand we are in a long-term contest, especially with China. It begins to re-anchor our economic and industrial base. It seeks to reduce overextension and force more burden-sharing. Those are all necessary.

The next step is to ensure that, as we adapt, we are not just grabbing nearby territory, but shaping a board on which our alliances are strong, our influence is connected, and our competitors find themselves quietly, steadily surrounded.

That is how you win at wéiqí. And in a world of strategic competition, it is how you win without firing a shot.

In line with my belief that responsibly embracing AI is essential to both personal and national success, this piece was developed with the support of AI tools, though all arguments and conclusions are my own.

Author

Mark Kennedy

Director & Senior Fellow