“Whites make locomotives; Negroes cannot make simple needles”

The poor can’t sleep

Because their stomachs are empty.

The rich have full stomachs,

But they can’t sleep

Because the poor are awake.

-Copper miner

Lusaka, Zambia

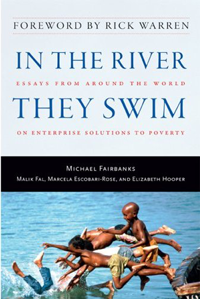

I have been privileged to work with some of the poorest people in the world in South Sudan. Their daily life is a constant struggle to feed, shelter and clothe their families. I have been, quite literally, the rich person who couldn’t sleep. So I was pleasantly surprised to read In the River They Swim, a collection of essays edited by Michael Fairbanks, Malik Fal, Marcela Escobari-Rose and Elizabeth Hooper, providing first-person case studies in going from poverty to prosperity that are informative and inspiring.

The title is based on a Sufi anecdote about three ways to know a river: to read about it, take a long journey to see it, or to enter it and be surrounded by the reality. Each essay plunges the reader into the river of being poor and overcoming it. Each essay left me wanting to hear more from the author, (except Rick Warren, author of the foreword).

The essays are not intended to be systematic or comprehensive and often leave the reader hanging with unresolved issues, much like real life (and unlike most aid reports). For example, Eric Kacou’s essay “Deciding What Not to Do” gives insight into a trade policy decision a Minister of Trade has to make (or not) that can substantially affect the financial progress of his country and the livelihood of five hundred thousand of coffee-growing families. The essay leaves the reader hanging as the author prepares for a meeting …

The book aims to be “the antithesis to the search for solutions in the next big theory of global poverty.” Instead it powerfully illustrates the power of individual creativity and resourcefulness.

Malik Fal, a Senegalese executive for PepsiCo in east Africa, describes his family’s struggles with poverty and racism in “Locomotives, Needles and Aid.” His father’s school experience under colonial rule included a teacher’s daily denigrating assertion, “Whites make locomotives; Negroes cannot make simple needles. Whites are civilized; Negroes are savages.” As his father “earned everything the hard way,” he worked his way through French engineering school, rising out of poverty through hard work. Malik compares the challenges of his father with his post-colonial business experience where Africans still struggle to receive equal treatment. Yet he himself overcame the odds anyway.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality