Giving Us Idiots More Credit than We Deserve

While not a complete idiot, I still find books in the "Complete Idiot’s Guide” series amusing and occasionally useful. So when The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Giving Back came out recently, I was curious to read the book’s recommendations.

The author outlines a process for deciding which causes to support, how much to give, and other factors to consider before giving a not-for-profit your hard-earned cash. Unfortunately, most idiots, and many other well-meaning people besides, will not read this book, but will respond to heart-wrenching pictures of children to decide which charity qualifies.

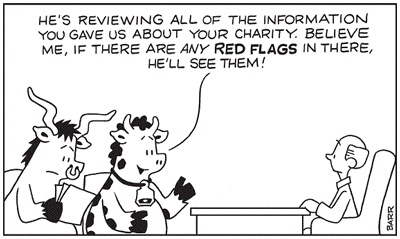

Even more unfortunately, reading this book isn’t going to make it much better. The author does counsel potential donors to devise and execute a giving plan. The chapter “Shopping for Charity” is particularly pointed in caveat emptor advice, interpreted here as "let the donor beware," but fails to provide enough guidance for idiots (or anyone else, for that matter) to truly evaluate the effectiveness of a charity.

On the other hand, the book encourages donors to look for more than just that warm and fuzzy feeling, and to ask questions about cause marketing: how much of an item’s purchase price actually goes towards the cause being promoted? Is there an upper limit on how much will be donated? Do the donations also have to cover corporate administrative costs?

We learn that the idea of cause marketing did not spring fully-formed from the heads of Bob Geldof and Bono, but rather got its start in 1971, when George Harrison and Ravi Shankar put on a concert to benefit Bangladesh. Sir Bob does deserve the credit for scaling up the concept, recruiting big-name rock stars for his 1984 project, Band Aid, and bringing us “Do They Know It’s Christmas” and “Feed the World,” which remained the best-selling single of all time in England until 1997. With his (RED) campaign, Bono refined the concept by leveraging his celebrity status to promote particular products, some of the proceeds of which go to the Global Fund.

The author directs readers to “Check out the Charity” but limits guidance to annual reports and IRS forms and how to identify a scam, providing insufficient tools to evaluate charities effectively. The author confesses that it is often challenging to unearth the amount actually donated to the designated cause. How well we know!

The book also fails to differentiate between charity at home and abroad. For example, the author’s advice on donating used goods may apply when the recipients of lightly used T-shirts and tennis shoes live halfway across the city, but the situation gets rapidly more complex if the charity plans to ship those goods abroad. The international landscape is more complicated than the scant references to issues like fair trade purchases and disaster relief imply. Looks like this blog still has a role to play.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality