The secret to success is failure

When Jacqueline Novogratz, founder of the Acumen Fund, was in her early twenties, she turned down a promotion on Wall Street and went to the Cote d’Ivoire to open a new branch of the African Development Bank focused on microfinance for women. But the West African women she was supposed to work with shunned her. They talked about her derisively in her presence, letting her know exactly what they thought of an untested, unmarried, American woman with poor French skills being sent to lead them. They intimidated her, locked her out of the office, and (Novogratz suspects) actually gave her food poisoning to scare her away. It worked.

On her next assignment, in Nairobi, she spent hundreds of hours analyzing the loan portfolio of a young microfinance organization. Presenting her results, she recommended a drastic restructuring. A week later, she found her handwritten report had been “lost,” and all her work destroyed.

When Jacqueline Novogratz, founder of the Acumen Fund, was in her early twenties, she turned down a promotion on Wall Street and went to the Cote d’Ivoire to open a new branch of the African Development Bank focused on microfinance for women. But the West African women she was supposed to work with shunned her. They talked about her derisively in her presence, letting her know exactly what they thought of an untested, unmarried, American woman with poor French skills being sent to lead them. They intimidated her, locked her out of the office, and (Novogratz suspects) actually gave her food poisoning to scare her away. It worked.

On her next assignment, in Nairobi, she spent hundreds of hours analyzing the loan portfolio of a young microfinance organization. Presenting her results, she recommended a drastic restructuring. A week later, she found her handwritten report had been “lost,” and all her work destroyed.

Any other 24-year-old might have gone home. For Novogratz, these heartbreaking episodes led to some profound revelations:

“I wanted to help,” she writes, “but that didn’t matter to anyone but me.” “Donors could convince themselves to give to nonperforming organizations based on a few good stories. The world needed something better than that.”

But the failures didn’t end there. She spent two months reviewing a UNICEF-funded loan program for income-generating projects in Kenya. She found hundreds of broken maize mills, empty schools and unsold baskets: countless “well-intentioned projects gone wrong,” a system riddled with kickbacks, and no accountability. In the end, government officials found her report “too pessimistic.” A World Bank official in Gambia rejected her proposal to lend to small businesswomen instead of giving them grants, using then-conventional wisdom that the very poor couldn’t pay back loans.

As Tom Watson, the founder of IBM, famously said, “if you want to succeed, double your failure rate.”

Because eventually Novogratz found big successes, like the bakery in Kigali where she helped a group of unwed mothers wean their operation off charity and become a real business. And Duterimbere, a micro-lending organization strong enough to survive the genocide in Rwanda.

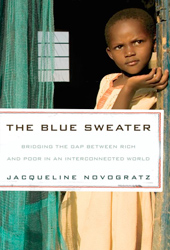

Not to mention the success of the eight-year-old Acumen Fund, which Novogratz calls a “nonprofit venture capital fund for the poor.” Just as Acumen absorbs the depth and breadth of her experiences and the advice of her mentors, the strength of this deeply personal book lies in its rejection of simplified narratives, easy truths and personal dogma.

Novogratz has emerged as a leading voice of a “middle way” in development thinking: “Philanthropy alone lacks the feedback mechanisms of markets, which are the best listening devices we have; and yet markets alone too easily leave the most vulnerable behind.” She writes:

I’ve learned that many of the answers to poverty lie in the space between the market and charity and that what is needed most of all is moral leadership willing to build solutions from the perspectives of poor people themselves rather than imposing grand theories and plans upon them.

So read this book! It documents in wonderful detail this resounding and inspirational conclusion.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality