Human Development Index Debate Round 2: UNDP, you're still wrong

by Martin Ravallion, Director of the Development Research Group at the World Bank

Francisco Rodriguez has defended the HDI against recent criticisms by Bill Easterly and Laura Freschi, who drew in part on my new paper, “Troubling Tradeoffs in the Human Development Index.”

Francisco would make a good lawyer, since he defends his case vigorously on multiple fronts. But this leaves a puzzle about his true position. On the one hand he claims that tradeoffs—including the implied monetary valuations of extra longevity and schooling—are not relevant to the HDI, and that it is even “incorrect” to calculate them. But (on the other hand) he agrees that the old HDI was deficient because it assumed constant tradeoffs (perfect substitution). If he does not care about the HDI’s tradeoffs then why does he care about how much substitution is built into the index, which is all about its tradeoffs?

The tradeoff built into any composite index is just the ratio of the (marginal) weight on one of its underlying variables (such as longevity in the HDI) to another (such as income). There is nothing “incorrect” in wanting to know the HDI’s weights and implied tradeoffs. These are key properties for understanding and assessing any composite index.

And the implicit weights and tradeoffs in the new HDI are questionable. I find that the HDI’s valuations of longevity in the new HDI vary from an astonishingly low $0.51 for one extra year of life expectancy in Zimbabwe to $8,800 in Qatar. The valuations are lower than for the old HDI, especially in poor countries.

And this striking devaluation of longevity is not just due to the fact that the HDI puts declining marginal weight on income, as Francisco suggests. As my paper shows, the weight on longevity itself has declined due to the change in methodology, and substantially so in poor countries.

Francisco defends the new HDI on the grounds that it allows imperfect substitution between its components. This is a non sequitur. One can introduce imperfect substitution without the questionable features of the new index. Indeed, I showed in my paper that if the HDI had used instead the Chakravarty index—a simple generalization of the old HDI, with a number of appealing properties—it could have relaxed perfect substitution in a less objectionable and more transparent way.

I agree with Francisco that perfect substitutability was a dubious feature of the old HDI, and (as he points out) the index was criticized from the outset for this feature. It is a shame that it took 20 years for the Human Development Report to fix the problem. And it is an even bigger shame that the proposed solution brought with it new concerns.

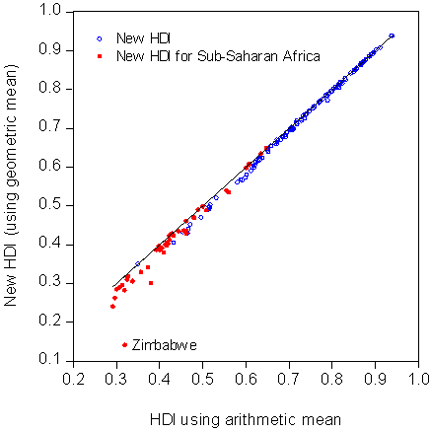

One such concern is the substantial downward revision to the HDI for many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which Easterly and Freschi pointed out. Francisco questions their claim, but the data are not on his side. The graph shows the pure effect of the change in the HDI’s aggregation method. (I have held everything else constant, at the same data used by the 2010 HDI.) Switching to the geometric mean involves a sizeable downward revision for countries with low HDIs, and these are disproportionately found in SSA.

This is not to deny that much of SSA is lagging in key dimensions of development, as Francisco notes. The point here is to separate the role played by the questionable new methodology used by the HDI.

Maybe it is time to go back to the drawing board with the HDI. Deeper consideration of what properties the index should have—especially its tradeoffs—would be a good way to start.

--

Related posts: The First Law of Development Stats: Whatever our Bizarre Methodology, We make Africa look Worse What the New HDI tells us about Africa Human Development Index Debate Round 2: UNDP, you’re still wrong

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality