Hey, fellow committee member, are you the weakest link?

UPDATE: 12:18 PM SEE END OF POST

I was just on a committee that selected a small number of papers from a large number of submissions for a conference. We each graded each paper and then we had to come up with a rule to go from our individual grades to a ranking of the papers to decide which ones got into the conference. So here are some possible rules:

I was just on a committee that selected a small number of papers from a large number of submissions for a conference. We each graded each paper and then we had to come up with a rule to go from our individual grades to a ranking of the papers to decide which ones got into the conference. So here are some possible rules:

(1) one veto kills the paper

So the overall grade for the paper equals the minimum of all of our grades, so if even just one of us flunks the paper, the paper flunks. You need to satisfy all of us. In econ lingo, you can't SUBSTITUTE one of us with a positive opinion for another one of us with a negative opinion.

ANALOGY: the "weakest link" production function, in which whatever input the economy has least constrains the whole output. Note that zero substitution means that all inputs/committee members are perfect complements. This is the world view of those who like Big Pushes to increase all the development inputs at once.

(2) simple average

Averaging our grades goes to the other extreme of perfect SUBSTITUTION between us. One of us with a positive opinion cancels out (i.e. substitutes for) another one of us with a negative opinion. We committee members are not complements at all: the value of my grade is not influenced by your grade.

ANALOGY: the old Human Development Index.

Also in production functions relating Development to inputs, this rule implies extreme flexibility. Rich economies feature this selectively to compensate for weakest links -- if the whole system is going to fail because of one input, then have a backup input that is a perfect substitute.

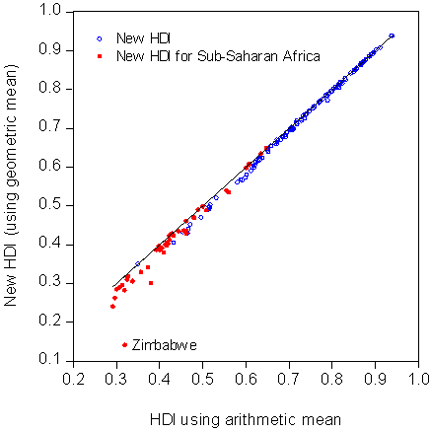

(3) geometric averages

This exotic animal (cube root of the 3 grades multiplied together) is in between (1) and (2). You can partially but not completely substitute for one of us with another one of us. So for example if we were just grading A,B,C (numerically 3,2,1), then a paper with the score (2,2,2) has a higher geometric average than a paper with the grades (3,1,2) although they both had the same simple average under 2. We are also partial complements -- the higher is your grade, the stronger is the effect of my grade.

ANALOGY: the new Human Development Index, which an Aid Watch post criticized for TOO MUCH complementarity. The higher was committee member Per Capita Income, the stronger was the effect of another committee member Life Expectancy, which has the unappealing property that we value lives of rich people far more than those of poor people. Makes more sense for production functions than for HDI.

The ending of the actual committee story-- qualitative discussions were necessary for choosing the final papers in the end after constructing the mechanical indexes. Let me see what is the analogy here...

UPDATE: thanks to both of you for reading this wonky post all the way to the end. Do you think I have atoned for that Swimsuit Edition post now? and even the followup Swimsuit Edition post also?

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality