“Proofiness:” trashing back on FAO hunger numbers

Just before the big UN meetings here in New York around the Millennium Development Goals, the FAO released new world hunger numbers, and Aid Watch listed reasons to worry that these numbers were “made up.” A blog post from Oxfam GB’s Duncan Green called our post “lazy and supercilious,” with the amusing headline “Easterly trashed.” The accusation that I am “lazy” struck a raw nerve, and so I have responded forcefully by asking Laura to do more work.

A closer look at the FAO’s documents, along with information provided by smart Aid Watch commenters as well as the FAO’s own senior economist David Dawe validates, rather than “trashes,” many of the concerns Aid Watch raised.

For one, the methodology for the FAO survey numbers does not actually directly measure malnutrition but tries to estimate it indirectly based on a model of human calorie requirements and food availability and distribution:

From the total calories available, total calories needed for a given population, and the distribution of calories, one can calculate the number of people who are below the minimum energy requirement, and this is the number of undernourished people.

A modeled number is NOT the same as directly measuring malnutrition (as the WDI anthropometric numbers cited in the previous post attempt to do). Is the model correct? How did they test it? A model has many assumptions and parameters, which are inevitably less than 100 percent reliable. All of these make the modeled numbers subject to a LOT of uncertainty. Has FAO made any attempt to quantify the uncertainty? Have they tried comparing their estimates to the anthropometric measures in WDI?

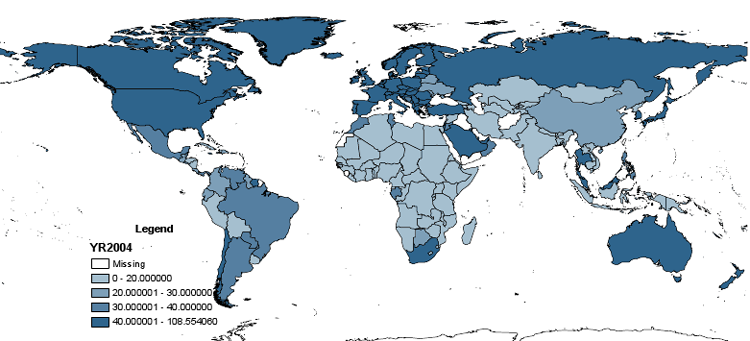

Second, according to the FAO’s downloadable data charts, this exercise was last carried out in 2005-2007. These survey numbers are available for every country in the database (176 in all). The data tables tell us that while there is no country-level data for Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia or Papua New Guinea, they are included in regional estimates, and there are country-level entries for places like Sudan, Zimbabwe and Libya for each three-year data collection period going back to 1990.

Neither of the most recent FAO State of Food Insecurity reports, from 2009 or 2008, includes discussions of the methodology for the 2005-2007 surveys. And neither explains how the 2008 figures were obtained. The 2009 report’s tables list as sources UN population data from 2006, and “FAO estimates” for undernourishment.

Third, the estimates for 2009 and 2010 are not only based on very indirect and noisy links between capital flows, imports, terms of trade and food availability, but the numbers for the former are not real numbers but based on USDA projected scenarios using IMF estimates for quantities that are notoriously difficult to estimate or project.

The comments from FAO economist David Dawe suggest (quite logically) that the economists, statisticians and policy-makers responsible for the FAO numbers are well aware of the drawbacks of the methodology they’ve chosen to produce both the survey year data and the estimates for years with no surveys at all; entire conferences and volumes are devoted to debating how to measure food deprivation.

Of course, none of this ambiguity and caution makes it into the papers. The New York Times reported simply that the UN said Tuesday, September 14 that the “the number of hungry people fell to 925 million from the record high of 1.02 billion in 2009,” but that “the level remains higher than before the 2008 food crisis.”

An alternative narrative based on the above would be something like: “the UN attempted on Tuesday to provide some projections for 2010 of the number of hungry people in the world compared to previous projections for 2009, all of which are in turn based on a combination of remarkably shaky links to other projections of impossible-to-project factors like capital flows, unverified and uncertain models of hunger and food availability, an unexplained estimate for 2008, and a survey of uncertain coverage and usefulness last conducted in 2005-2007.”

A new best-selling book called Proofiness opens with a quote that we are “vulnerable to the belief that any alleged knowledge which can be expressed in figures is in fact as final and exact as the figures in which it is expressed,” then the rest of the book explains why this “proofiness” is really “mathematical deception.”

Aid Watch will continue its lazy and supercilious attacks on proofiness.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

Clive Crook is such a calm, sensible, non-ideological voice, that if you ever get him really upset, you're in deep trouble. And he could hardly contain himself at

Clive Crook is such a calm, sensible, non-ideological voice, that if you ever get him really upset, you're in deep trouble. And he could hardly contain himself at