Does health aid to governments make governments spend more on health?

If you’re not an economist, you might reasonably assume that the answer to this question is yes. The story might go something like this: aid agencies give money to poor country governments to distribute bed nets or give vaccinations, and those additional funds are added to whatever money the country was able to scrape together to spend on health before the donor came along. As a result of the health aid, the total amount of money spent on health increases. There is new evidence, from a study from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation published in the Lancet last week, showing that this story doesn’t describe what’s really going on. Overall, global public health financing shot up by 100 percent over the last decade, but the study’s authors found that on average, for every health aid dollar given, developing country government shifted between $.43 and $1.17 of their own resources away from health. The trend is most pronounced in Africa, which received the largest amount of health aid.

The finding that health aid substitutes for rather than complements existing government health spending has caused a mini- scandal in the press precisely because it runs so counter to people’s optimistic expectations, perpetuated by aid agencies’ fund-raising campaigns, about the level of control that donors can exert over the spending of developing country governments.

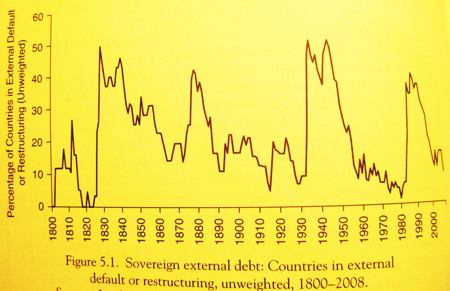

Economists, on the other hand, have been beating the dismal drum for a long time on this issue. In 1947, Paul Rosenstein-Rodin, then a deputy director at the World Bank, famously said, “When the World Bank thinks it is financing an electric power station, it is really financing a brothel.” Economists expect that aid will be at least partially fungible (that is, that aid money intended by donors for one sector or project can and will be used by governments interchangeably with funding for other priorities), and this prediction is borne out by empirical studies from the late 1980s on. The authors of a 2007 paper in the Journal of Development Economics observed, “While most economists assume that aid is fungible, most aid donors behave as if it is not.”

You might argue (as Owen Barder does in depth here) that recipient governments are acting rationally in response to erratic donor funding, which ebbs and flows according to donor priorities and how well the global community mobilizes fundraising around a particular issue in any given year. After all, doesn’t the donor community’s insistence on country ownership mean that they want poor country governments to be able to set their own budget priorities?

The problem is that aid agencies have long used the argument that earmarking aid for a specific project or sector is a credible way to force recalcitrant recipient country priorities into line with donor priorities—to coerce bad governments into making good decisions.

If governments that don't prioritize their people's welfare respond to an influx of aid money by simply shifting their existing resources around to circumvent donor priorities (and we don’t know what is happening to the resources shifted away from health—they could be going to private jets and presidential palaces, or to education, infrastructure, or loan repayments, or really anything at all), then the aid agency argument for project aid falls apart. The burden of proof correctly lies with the aid agencies to show that aid isn’t freeing up funds for bad governments to use badly.

The Lancet findings are scandalous, relative to the naïve but widespread belief that donors can use earmarked aid to force bad governments to behave.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

The Defense Department just sponsored a contest in which they randomly placed 10 large red balloons across the United States and challenged teams to find them all. The one who found all 10 first would get $40,000.

The Defense Department just sponsored a contest in which they randomly placed 10 large red balloons across the United States and challenged teams to find them all. The one who found all 10 first would get $40,000.

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal

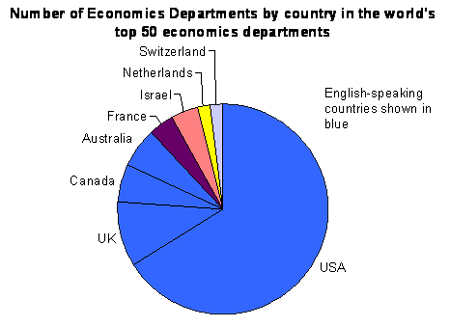

We see Beyoncé specializing in music videos, which she trades to Bill Gates for his specialized production of software. We will get more of both music videos and software from Beyoncé and Gates than if each (without the possibility of trade) had been forced to supply their own needs for software and music videos.

We see Beyoncé specializing in music videos, which she trades to Bill Gates for his specialized production of software. We will get more of both music videos and software from Beyoncé and Gates than if each (without the possibility of trade) had been forced to supply their own needs for software and music videos.