The parable of uneven growth

You’re in a multi-lane tunnel, all lanes in the same direction, and you’re caught in a serious traffic jam. After a while, the cars in the other lane begin to move. Do you feel better or worse?

Though it may sound like a description of New York traffic after last night's snow storm, this is in fact NYU Economics Professor Debraj Ray’s analogy (adapted from Albert Hirschman’s early work on economic development) about the response to uneven growth in unequal societies:

At first, movement in the other lane may seem like a good sign: you hope that your turn to move will come soon, and indeed that might happen. You might contemplate an orderly move into the moving lane, looking for suitable gaps in the traffic. However, if the other lane keeps whizzing by, with no gaps to enter and with no change on your lane, your reactions may well become quite negative. Unevenness without corresponding redistribution can be tolerated or even welcomed if it raises expectations everywhere, but it will be tolerated for only so long. Thus, uneven growth will set forces in motion to restore a greater degree of balance, even (in some cases) actions that may thwart the growth process itself.

In this same paper, Professor Ray argues that economic growth in developing countries has recently been “fundamentally uneven”: some sectors in an economy initially grow more quickly than others, which allows some groups in society to benefit while others lose out. When, where, and why uneven growth leads (destructively) to frustration or (constructively) to higher aspiration is a puzzle whose answer determines how well societies will adapt to change and sustain growth.

His tunnel parable made me think of Andy Sumner’s recent finding that three-quarters of the world’s poor now live in middle-income countries, a big change from 30 years ago, when 90 percent of the poor lived in very poor countries. This means that far more of the people stuck in the slow lane may now also be watching their neighbors break free of the gridlock and cruise away.

--

See also: Development is uneven, Get over it.

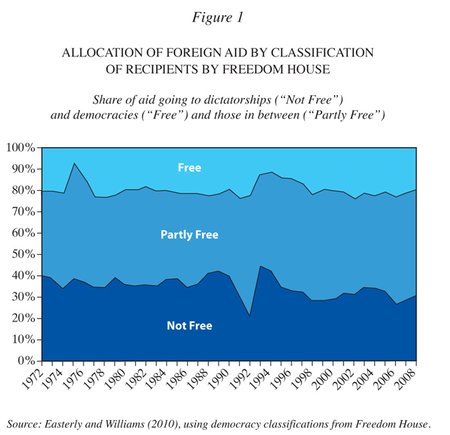

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality